How does Self Portrait in Tuxedo by Max Beckmann stand out among his many self portraits?

- James Bond in a mask

- The rebellious New Objectivity movement

- An avant garde art world figure

Click here for the podcast version of this post.

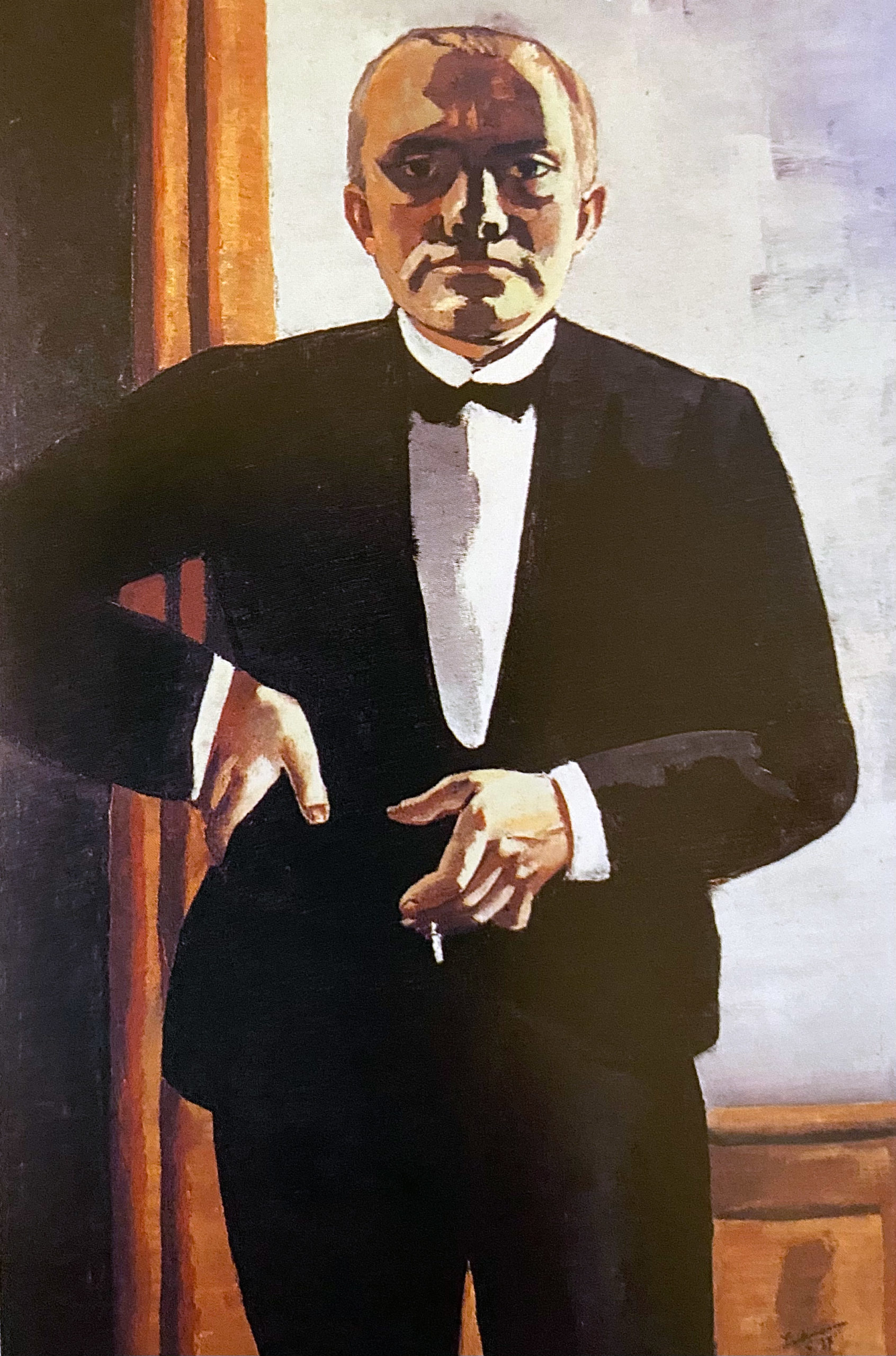

Max Beckmann stands for individualism. He exemplifies this in his Self Portrait in Tuxedo painting. It’s a remarkable, almost masked portrayal that reveals Beckmann’s desired persona. He was an avant garde painter. But not in the typical modes of his peers. Beckmann painted in the early 1900s. Most avant garde artists of the day worked in a non-representational mode. That means they portrayed intangible subjects rather than familiar or figurative ones. Such artists moved away from direct representations of reality. It’s why many of us think of abstract artwork when we hear the term avant garde.

Abstraction was only part of the reason this group of artists were avant garde, though. There’s a lot more to avant garde art than subject matter. Beckmann illustrated this with his figurative subjects and avant garde ways. That individualist spirit pervades Self Portrait in Tuxedo. Viewers can’t nail Beckmann down into a particular style or even persona. He crosses all boundaries. That’s evident in his artwork as well as his presence here.

What kind of painter wears a tuxedo? His features hide behind a mask of shadow. This shielded face tells us he’s not giving us clues about the man behind the art. That’s a rather avant garde take on a self portrait. Here I am, it seems to say, behind this mask and formal wear. He keeps us guessing.

Self portraits weren’t new to Beckmann. This was one of about forty he painted during his career. Self Portrait in Tuxedo distinguishes itself from the rest with distinctive choices. For instance, the painter stands before an open door. He also crops off an elbow from one arm and dangles a cigarette in the hand of the other.

Max Beckmann’s Surface Tension

The door behind Beckmann stands open for Self Portrait in Tuxedo. It’s a direct contrast to the painter’s persona here. He’s closed for business and cut off. That’s a literal reference. Beckmann dressed himself in formal wear for this pose. It’s a costume, as if he’s a businessman attending an event. Truth is, he’s an artist. The only occasion here – posing for himself. He’s also cut off his elbow on our left. Beckmann won’t give us his whole body. So, we get a facade of a man and not even all of that. He opens the door but also obscures his figure behind layers of surface tension. In this way even Beckmann’s setting is a false pretense.

Brands have trademarks. Like such a concocted product for sale, Beckmann too has a symbolic logo. His dangling cigarette, central to this painting, signals his artistic persona. It’s often pointed to as his “trademark”. This prop tells us little about him, though. In fact, smoking presents yet another idea of a disguise. Smoke works as a blurring shield between people – a literal smokescreen. Self Portrait in Tuxedo doesn’t need literal smoke here. The cigarette serves as its signature instead. This reminds us that Beckmann loves to smoke and stands behind his cigarette’s veil.

Stance also tells the story of Max Beckmann’s Self Portrait in Tuxedo. The casual grace of his stature gives him a nonchalant vibe. It’s as if this portrait has little importance to him. This impression separates the figure in the painting from the artist. Of course, the figure means a lot to the man who paints it. So, the way he stands sets him apart from the artist part of himself. This caring, thoughtful, aspect of Beckmann remains offscreen. It may be in the other room – where the open door leads. After all, once he finishes the painting, the creator will disappear into the past. We’re then left with only his creation. That speaks for the painter and, in the case of a self portrait, stands in for them.

Self Portrait in Tuxedo presents the artist as a cool cat in formal attire. His face remains mysterious, behind a shadow. While the rest of this figure strikes a distinct pose. See this painting once and you’ll never forget that hip jut in a tux. Max Beckmann plants a seed in our mind of the mystery man artist. He’s James Bond with a paintbrush tucked into his back pocket.

Self Portrait in a Tuxedo – FAQs

What defined avant garde art in the early 1900s?

Many art historians would point to Expressionism as the key to avant garde. It’s accurate. But there’s more to this movement than one category. The primary focus of the avant garde was to change how we look at art. To be specific, one must assess the artist’s vision and ideas for both quality and originality.

Subject matter or portraying its reality take a backseat with the avant garde. Max Beckmann’s Self Portrait in Tuxedo – 1927 illustrates this to perfection. It doesn’t matter that it’s yet another self portrait. Nor does the artwork even try to match objective reality well. Yet, it’s an avant garde masterpiece. That’s because it expresses original ideas about art and what it means to be an artist.

Why was Max Beckmann an important painter?

The best thing about Max Beckmann and his work are the way both cross boundaries. He can’t be defined and his art blends categories. That’s his hallmark – individuality. Art historians tend to call Beckmann an Expressionist. That would infuriate him …if he could hear them.

He rejected the Expressionist label. In fact, Beckmann played a major role in the offshoot of Expressionism called the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit). This countered Expressionism’s abstract and internalized focus on emotions. New Objectivity was much more Beckmann’s style. But that doesn’t mean he would have welcomed this label either. He didn’t like definitions.

In what category of art does Max Beckmann’s work fit?

We’ve already explored the lack of categories suited to Beckmann himself. His work also fits into various divisions. One reason for this was timing. Max Beckmann was a German artist during the Weimar Republic. It was a volatile time for everyone – especially Germans. Hitler rose to power from this chaos.

German artists responded to the societal upheaval with a cultural renaissance. Expressionism, Impressionism, and Cubism were all the rage. That’s why many slip Beckmann into the Expressionist slot – this precise timing.

But his work isn’t much like most Expressionists. Also, he helped springboard the New Objectivity sub-category of Expressionism. This subdivision represented a rebellious offshoot. The New Objectivists rejected the naval-gazing emotionalism of the Expressionists.

ENJOYED THIS Self Portrait in Tuxedo ANALYSIS?

Check out these other essays on German Painters

Check out Self Portrait in Tuxedo at the Harvard Art Museum

Belting, Hans (1989). Max Beckmann: Tradition as a Problem of Modern Art. Preface by Peter Selz. New York.

Michalski, Sergiusz (1994). New Objectivity. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen.

Klein, Lee (2003). “Art on the Eve of Destruction”. PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art.

Reimertz, Stephan (2003). Max Beckmann: Biography. Munich.

Tobias G. Natter (ed.): The Self-Portrait: From Schiele to Beckmann., exhibition catalog Neue Galerie New York, Munich e. a.: Prestel, 2019

Gay, Peter (1968). Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider. New York: Harper & Row

Nicholls, Anthony James (2000). Weimar and the Rise of Hitler. New York: St. Martin’s Press.