What makes the Aaron Douglas painting From Slavery Through Reconstruction significant?

- Harlem Renaissance revival murals

- The watermarks of yesteryear teach us today

- Racism and Outcry in From Slavery Through Reconstruction

Click here for the podcast version of this piece.

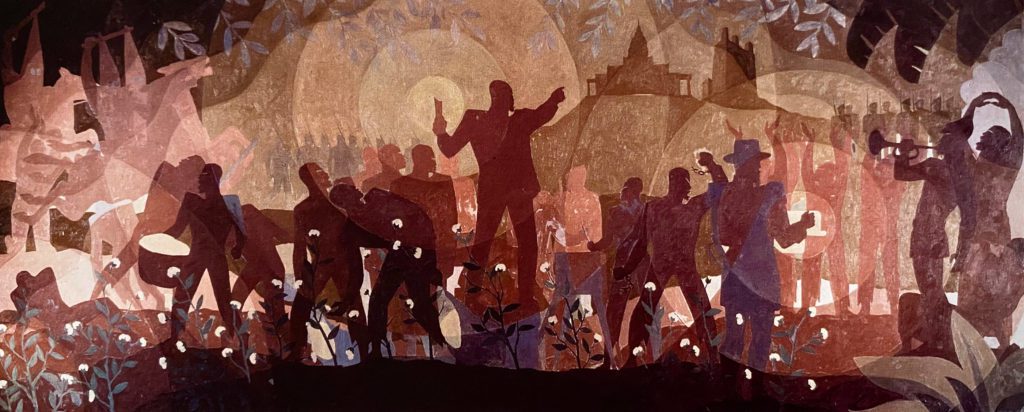

From Slavery Through Reconstruction answered a crucial calling. It was 1934 – peak of the Great Depression. The philosopher Alain Locke’s entreaty for Black stories inspired the Harlem Renaissance. Aaron Douglas was one of the artists who filled this need. The Federal Arts Project funded him with a New York Public Library project. The mission: create murals about the African American experience. This painting focuses on African Americans after the Civil War. Douglas reveals a transition from the left side of the painting to the right. It represents traveling from pre-war South to the post war North.

Viewers can discern this from reading the symbols and movement across the canvas. There’s a subtle artistry in his technique here. Two visual examples remind me of modern day watermarks. On the left, his KKK on horseback seem to ride on an ink undercurrent. White on shadow. Also, sonic circles radiate from the center and right side with filmy waves. These are the underlying themes – racism and outcry. Like a watermark, they’re omnipresent. Douglas reminds viewers what’s always lurking for Black Americans.

The KKK figures point to inherent oppression that drove former slaves to head North after the war. I love how Douglas gives them an ominous transparency. They’re the only white figures in the piece. Yet the KKK are also the only people who seem like shadows. The black figures are more tangible in From Slavery Through Reconstruction. Some mourn or march like the soldiers near the horseback KKK. Others entertain, cheer and proclaim. But no matter what they do, all are 100% full bodied.

The circle booms are significant because they represent the Black community uproar. In the center a man holds the Emancipation Proclamation in one hand and points toward D.C. with the other. The rings of sound emanate from this core to spread the word. Use your newfound power – go vote. To the right we find another strong message – celebrate your freedom. Here the coils represent musical loops. Behind them a conductor leads musicians while others cheer. Each of these spheres spotlight the leaders in From Slavery Through Reconstruction.

These leaders each urge their people to action. I love the stance of the man at center. He holds the Emancipation Proclamation like it’s a ticket. With a newfound power to vote, Black Americans could impact policies and shift systematic racism. His other hand points to where everybody needs to direct their attention – the U.S. Capital.

The conductor on the right leads the celebration. He stands at a white lectern and holds a hand up in a gentle gesture. Those he leads have their arms high in the air. There’s a trumpet pointed up, a dancer with limbs lifted in an oval toward the sky, and a celebrator cheering. These are joyful, free, people. From Slavery Through Reconstruction is the hopeful piece in this series of murals.

Aaron Douglas – Father of Black American Art

These Douglas murals tell a comprehensive story. They also bear the dated name Aspects of Negro Life. These masterworks reveal a Black American hope and resilience that is relevant even today. The first piece in this four-part series sets subjects in Africa. It’s a jubilant, dancing scene with African sigils and imagery. Aaron Douglas combines rhythmic silhouettes on a soft blend of pale pastels. This technique boosts the impact of strong figural imagery. It also sets the scene as gentle, lush, and comfortable. There’s a sense of joy in this first piece. Douglas uses this same silhouette method throughout the series. But the tone shifts.

From Slavery Through Reconstruction comes second in the series. This scene portrays a starker use of silhouette. The background feels more like fire and turmoil. While black figures remain solid and strong. Their straight back stances and confident gestures show positivity. No matter the stage he sets, the artist’s figures remain steadfast in strength. There’s even a spiritual resonance and tenacity that transcends their locations. This piece illustrates a journey. Overwhelmingly, Douglas imbues the mural with promise.

He combines African art models with Synthetic Cubism. For instance, the cut out look overlaps his figures. So, they are intermixed as symbols. These include Egyptian reliefs and mural paintings. There are also references to sub-Saharan sculpture in the Douglas style. His distinctive vision fuses African and European art. From Slavery to Reconstruction becomes a map that reveals its own thematic territory.

It marks the midpoint for the mural series. That’s my favorite thing about it. In my childhood, school books concluded the Black American story here. The Emancipation Proclamation freed the slaves. That was the happy ending. These texts positioned the 60s Civil Rights movement as specific to Southern racism and inequality. Aaron Douglas helps correct this error.

His mural series expands the Black American story beyond From Slavery Through Reconstruction. In fact, the third piece depicts segregation and lynching in the post Civil-War states. His final mural then portrays a path to the Harlem Renaissance; ending the series on an inspiring image.

Aaron Douglas cemented his position as the father of Black American art. I wasn’t surprised that Douglas was an art educator as well as a painter. From Slavery Through Reconstruction teaches viewers while it moves us. These murals feel familiar and profound. Pure Harlem Renaissance. His powerful, personal, vision continues to inspire some of the foremost artists today. Acclaimed painters such as Kara Walker reference Douglas even now with buzzworthy effect. The conversation continues thanks to his legacy.

From Slavery Through Reconstruction – FAQs

What is the Harlem Renaissance?

The Harlem Renaissance filled the American 1920s and 30s with remarkable Black art and culture. This included literature, fine art, music, theater, and fashion. It started with Alain Locke’s anthology The New Negro in 1925.

Alain Locke was the first Black American Rhodes Scholar. He’s also noteworthy as a philosopher who inspired the Harlem Renaissance. His writing pointed to Harlem as an epicenter for Black American culture.

It was Locke’s work that convinced Aaron Douglas to stay in Harlem and focus his art there. His subsequent works, such as From Slavery Through Reconstruction, earned Douglas the title Father of Black American Art.

What defines Synthetic Cubism?

The Cubist style of painting included several iterations. The Synthetic period bridged “high” and “low” art. That’s because Synthetic Cubism was made by an artist but produced for commercial use.

Collage was common in this form of Cubism. Picasso and Georges Braque started this genre. They packed their pieces with bright colors as well as real items like playing cards or sheet music.

Where did Aaron Douglas create the series with the painting From Slavery Through Reconstruction?

Douglas was on his way to Paris when he stopped off in 1925 Harlem. Alain Locke’s writings about the Harlem Renaissance inspired him to visit. He then began working with the painter Winold Reiss. This elder painter suggested Douglas try Africa-centric themes in his work.

So, it was in Harlem that Douglas created paintings meant to unite the Black community with the art world. He lived, worked, and glorified the Harlem Renaissance.

ENJOYED THIS From Slavery Through Reconstruction ANALYSIS?

Check out these other essays on Black Artists.

Hornsby, Alton (2011). Black America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. Greenwood.

“Study for ‘Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery Through Reconstruction'”. The Baltimore Museum of Art. artbma.org.

“Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist”. Spencer Museum of Art.

Kirschke, Amy Helene (1995). Aaron Douglas: Art, Race, and the Harlem Renaissance. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

“Trials and Triumphs: ‘Aaron Douglas: African-American Modernist’ at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture”. The New York Times.

Driskell, David C.; Lewis, David L.; Ryan, Deborah Willis; Campbell, Mary Schmidt (1987). Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America. New York: The Studio Museum.

“Aaron Douglas”. Kansapedia. Topeka: Kansas Historical Society. 2003.