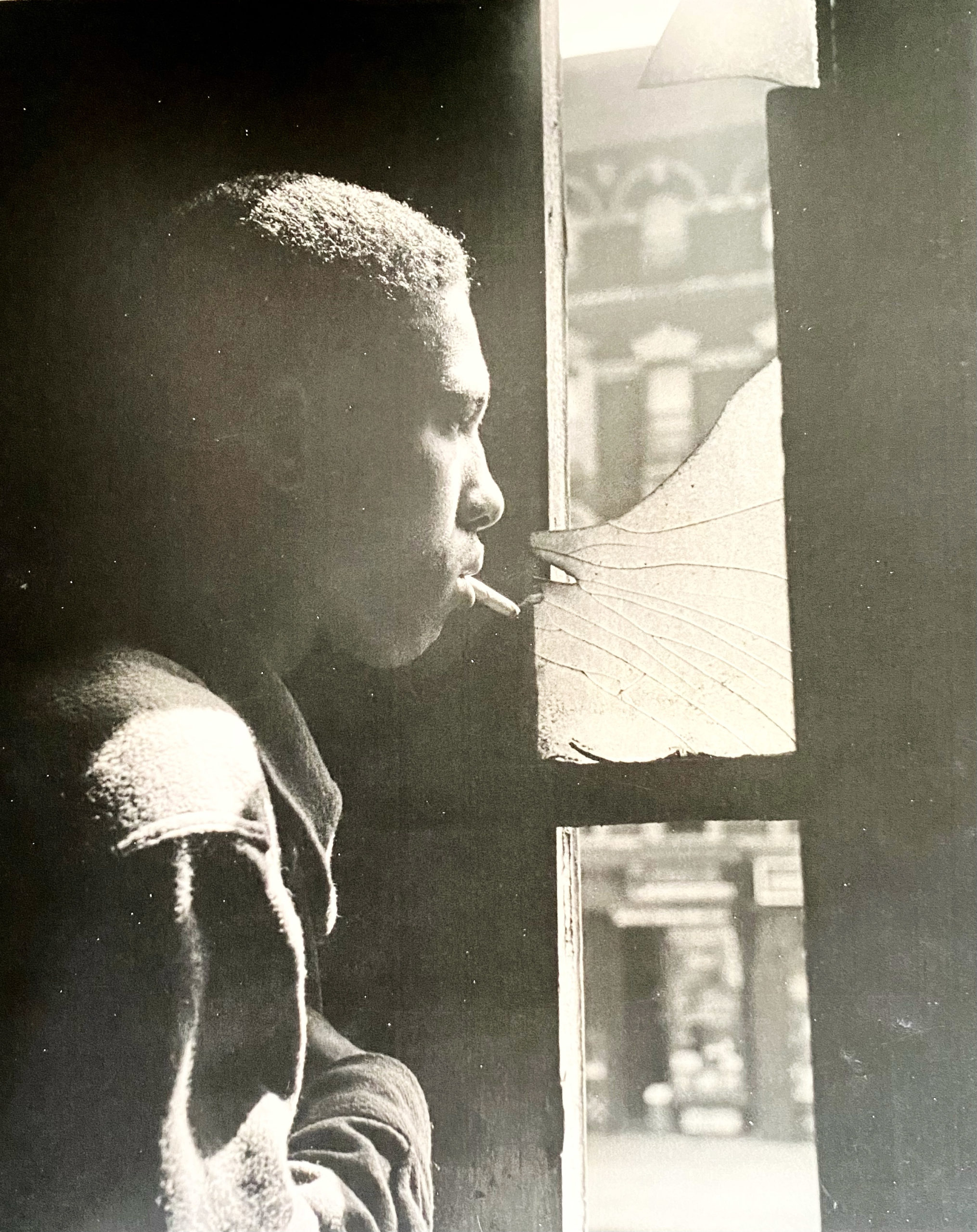

The Red Jackson photograph by Gordon Parks sent me into a whirlwind of reactions from the first time I saw it. Encountering this black and white masterpiece in the Metropolitan Museum of Art feels like a lucky break at first. It’s a thoughtful photographic version of a Vermeer that’s still fresh today, even though it’s from 1948.

Podcast version of this post.

When Parks took this picture he was working on a feature for Life magazine as a social documentarian. It was a piece about gangs in Harlem and the Red Jackson photograph stood out as an emblem of the story. Unfortunately, Life got the story wrong. They twisted the narrative to make it all about violence nearly to the point of blaxploitation. This must have been challenging for Park, a black photographer. But in the end, he created a masterpiece of modern photography. Even the iconic Life magazine can’t impede the lasting power of truly great art.

LadyKflo’s YouTube Summary

The photograph Red Jackson prevails as a masterpiece because it only gets better and more relevant as years go by. It stands the test of time as a luminous and haunting portrait of a man with a lot on his mind. This current perspective reads more relatable and timeless than Life magazine’s shallow take in 1948. The portrait seems to capture a sad moment looking through a broken window and into the light.

More than a Man

It’s about more than this man who was born Leonard Jackson and became Red Jackson as a gang leader. The portrait uses a gang title rather than his real name. At the time Life magazine wanted to highlight the man’s role in society rather than the man himself. But when we look at Leonard’s face and the light shining across it, it’s the man we contemplate.

The first time I saw Red Jackson it seemed more like he had a lollipop in his mouth rather than the cigarette dangling there. I don’t know if it was because Leonard has such a young face or the forlorn look upon it. But it took me a few moments to realize it was a cigarette, burning away. Then, once I saw it, the smoky surroundings within the frame took on a deeper meaning. The smoke seems to serve a visual purpose.

A filmy vagueness surrounds our subject with what seems like soft focus. This contrasts the sharp spike of broken glass pointing at his vulnerable face, pillowed in smoke. It also appears that Leonard holds his hand over his heart. These are the two actions viewers can see clearly – smoking and covering his heart. Both give him a sort of protection – one physical and the other emotional.

Broken Windows

Broken windows later became a symbol of poverty. Of course, windows break in all buildings, not only those of the disenfranchised. But in 1982 the broken windows theory was born in yet another esteemed magazine The Atlantic. Two social scientists came up with a corollary between broken windows and crime. But the inferences drawn were not based on any proven reality. Unfortunately, that didn’t matter much and the theory caught on. In fact, it was the basis for subsequent government choices about which neighborhoods to provide funding and which to monitor more.

A stunning example of this was Rudy Giuliani’s Broken Windows policy in mid 90’s New York City. This led directly into the Stop and Frisk procedures of the early 200os. Openly touted in their time, both of these practices are now noted for their fundamental discrimination against the black community.

Society’s overall perception of broken windows has shifted since 1948, when Gordon Parks created Red Jackson. The photograph, though, holds even more power today than it did about 75 years ago. I can’t help but see pain in Leonard Jackson’s face as he gazes through the broken window. Given the role he played at that time in society, a gang leader in Harlem and a black man in New York City, pain was a likely condition in his life.

The gentle manner in which Parks shows us this side of the man reminds us that pain is part of being human. After all, we all have our own version of a broken window at some point. This brings us a bit closer to Leonard Jackson, the man, and connects us to each other as well.

Red Jackson – FAQs

Why is Gordon Parks an important photographer?

Gordon Parks started his photography career working for the government, and then Life magazine. He took striking and poignant photos that often raised controversy as they exposed underlying inequality among Americans.

Some of his fine works such as Red Jackson started out as pieces of social documentary. But they’re now appreciated as fine art and grace the galleries of the world’s most esteemed museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What did Gordon Parks contribute to cinema?

Gordon Parks was more than just a photographer. He also co-created the blaxploitation film genre when he made the 1971 film Shaft as well as Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.

Although these films were exploitative and engendered harmful stereotypes, they also introduced black action heroes into the film world. This was an extraordinary feat in the early 1970s when there were also no other black filmmakers.

Enjoy this analysis of Red Jackson by Gordon Parks?

Check out more LadyKflo essays on fine art photography.

Sources

Lord, Russell (2013). Gordon Parks : The Making of an Argument. New Orleans Museum of Art, Steidl, The Gordon Parks Foundation.

“Gordon Parks”, “Inductees” section, International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum website.

Chenrow, Fred; Carol Chenrow Carol (1973). Reading Exercises in Black History, Volume 1. Elizabethtown, PA: The Continental Press.

An encyclopedic definition for the Broken Window theory

Lawrence W. Levine (December 1992). “The Folklore of Industrial Society: Popular Culture and Its Audiences”. The American Historical Review. American Historical Association.

Read more about Rudy Guiliani’s Broken Window policy

Brookman, Philip (2019). Gordon Parks: The New Tide: Early Work 1940–1950. Steidl/Gordon Parks Foundation/National Gallery of Art.

Zara, Janelle (November 16, 2021). “‘He’s inspired so many of us’: how Gordon Parks changed photography”. The Guardian.