What’s so special about the sculpture Woman Combing Her Hair 1915 by Aleksander Archipenko?

- A moving figural map

- The void within

- Futurist fundamentals in 3D

Click here for the podcast version of this piece:

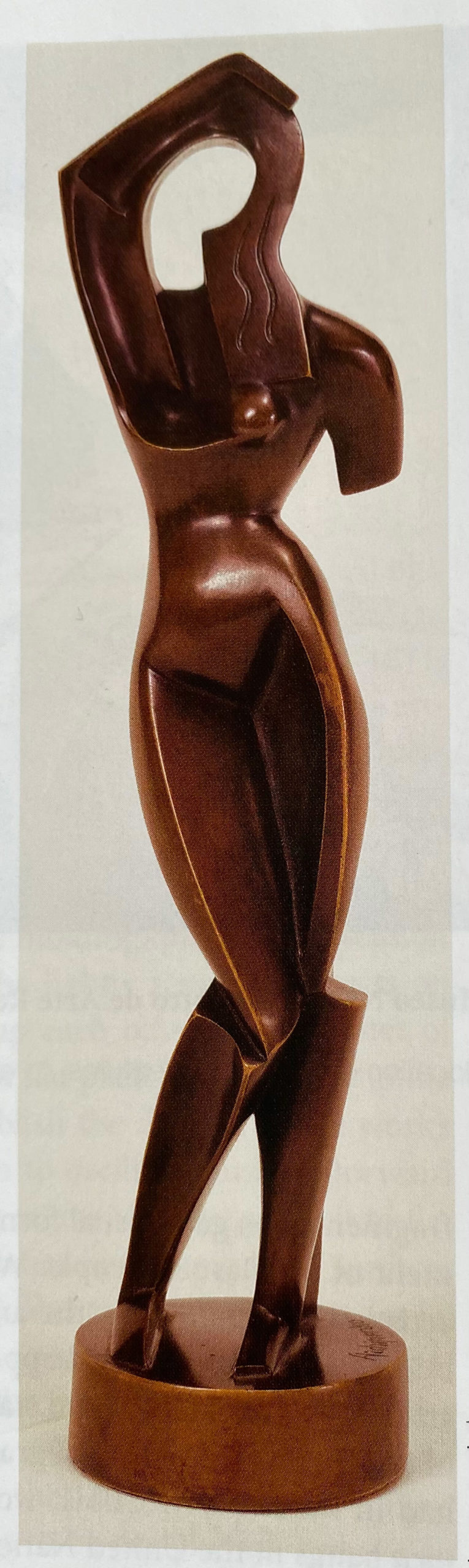

Spatial ambiguity meets bronze goddess in Woman Combing Her Hair 1915. Ukrainian sculptor, Aleksander Archipenko crafted it in the Cubist and Futurist heyday. We can see that in the way he relates the spatial planes of this figure. There’s a rhythmic connection between the parts. Yet they are also somehow fragmented. Archipenko presents the figural pieces with a magical sense. They fit like a puzzle. Best part is, the sculptor leaves a crucial bit out.

Woman Combing Her Hair 1915 shows how Cubism employs negative space. Archipenko left out the woman’s face. Still, viewers know she’s lovely. The spatial ambiguity of that facial void gives us a job to do. We’re armed with the curvaceous planes of her body as a map to guide the filling-in of that face. There’s fluidity to the form. It helps us imagine the caress of a comb through her hair. The sculptor guides us with each bronze curve in this body. Even as they seem disjointed, each piece works with all the others to create continuity.

Woman Combing Her Hair 1915 seems to flow with movement. She’s in action – as her title indicates. This makes sense because Archipenko created her in 1915. That’s when Futurism, with its movement obsession, rocked the art world. The sculpture swirls with intersecting planes like a Cubist painting. Also, the facial void interrupts the bronze flow – halting our viewer eyes as we scan the artwork. This adds complexity to the piece much like the way Cubist painters use negative space.

Archipenko broke with traditional boundaries. He left the face up to the viewer in Woman Combing Her Hair 1915. She seems to lift it up to bask in sunlight. An arm drapes around her head – grooming the area. This makes it easy to imagine fresh, combed, hair cascading down her back. I love the way her knee on our right pokes out a bit as if askew. It reminds me of grooming ticks, like biting a lip while applying eye makeup. We’re less conscious of our body’s actions while prepping and prettying ourselves. That natural element of human nature comes through thanks to Archipenko’s ingenuity.

The sculpture, Woman Combing Her Hair 1915 parallels the painting, Nude Descending a Staircase No 2. In fact, many elements link Archipenko’s sculpture with Duchamp’s masterpiece. For instance, both of these artworks exemplify Cubism and Futurism. They’re primo examples for exploring the complex relationship between forms and space. That’s crucial in Cubist artwork. Each of them also gives the illusion of movement using a fragmented, ambiguous, figure. This satisfies Futurist senses. Although undressed, these figures lack gendered body parts. As an artistic choice, it points out a fresh take on nude figurative art.

Traditional nudes focus on the figural body. Even innovations presented bodies with new ways of looking at the form. But Archipenko and Duchamp key into what the body does rather than the form itself. They give us movement to look at rather than body parts. Descending and combing are actions, after all. They’re also the true subjects of these artworks.

This locks both of these masterpieces into a Futurist concept. Futurism was a short-lived art movement of the early 1900s. It obsessed over movement and machinery. These two ideas sing through both of these artworks at equal volume. Woman Combing Her Hair 1915 looks like a curvy, articulated robot. She’s busy fixing her hair at the moment. But would fit into any science fiction story in need of a sensual, futuristic cyborg.

Rather than posing her, Archipenko set this woman into action. So, she seems of-the-moment, as if we caught her with a stop-motion camera. It keeps the sculpture feeling modern, even at a hundred years old. Duchamp’s Nude Descending has this spellbound magic too. The delineated figure descends with tiny, bionic steps. He holds our eyes rapt in the momentum of its robotic descent.

I recommend a visit to the MOMA in NYC. There you can see both artworks. Visiting them back and forth a bit, they seem more and more related. Of course, only two years passed between these two masterpieces. The later, sculptural form Woman Combing Her Hair 1915 seems softer. She’s meditative, maybe even rapturous, in stance. I always imagine her eyes are closed. Although this piece explores movement, it’s also a calm and soothing moment.

Woman Combing Her Hair 1915 – FAQs

Why is Aleksander Archipenko an important artist?

Often cited as “Alexander” in english publications, Archipenko brought Cubism to life with sculptures. He awakened formerly flat-on-canvas Cubist ideas with a shot of 3D magic. Only Picasso beat him to the punch on this. Archipenko pioneered Cubism.

He showed cutting-edge Cubist works in Paris; the Salon des Indépendants of 191o and Salon d’Automne in 1911. His signature contributions were innovative uses of spatial planes and negative space. The sculptor used voids to change the way viewers perceive a human figure in art.

Hold on… I saw Woman Combing Her Hair 1915 at the Tate, London. Why are you saying it’s at MOMA?

Much like Marcel Duchamp’s sculpture Cadeau – The Gift from the same period, Archipenko made several casts. He made a dozen casts for Woman Combing Her Hair 1915. The one at the Tate, London is the third. It’s a slightly duller cast, in my opinion. I find the one at MOMA quite shiny – even luminous in parts.

It fits the Futurist ideology to make several copies of artwork. This art movement revered all notions of what they deemed “progress”. Such concepts included machinery and mass production.

Why do so many artists portray women grooming themselves?

A woman at her “toilet” has been popular among artists through the ages. From antiquity through the Renaissance, and even today, there’s intrinsic appeal to this intimate peek. Such portrayals put the viewer into the role of voyeur.

In a way, this elevates the artist’s position in society. The artist has secret access to the private worlds of beautiful women. So, such portraits by Degas, Hashiguchi Goyo, or Guiseppe Crespi remind us that artists give us a lens into worlds we might not otherwise witness.

ENJOYED THIS Woman Combing Her Hair 1915 ANALYSIS?

Check out these other essays on Cubism

Herwarth Walden, Einblick in Kunst: Expressionismus, Futurismus, Kubismus. Berlin: Der Sturm, 1917

Herbert Read, A Concise History of Modern Sculpture, Praeger, 1964

Donald H. Karshan, Archipenko, Content and Continuity 1908–1963, Kovlan Gallery, Chicago, 1968

“Artist:”Alexander Archipenko” | Minneapolis Institute of Art”. collections.artsmia.org.

“Finding Aid”. Alexander Archipenko papers, 1904–1986, (bulk 1930–1964). Archives of American Art. 2011.

Alfred Hamilton Barr (1936). Cubism and abstract art: painting, sculpture, constructions, photography, architecture, industrial art, theatre, films, posters, typography. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Halich, W. (1937) Ukrainians in the United States, Chicago